The Healthcare Breakdown No. 010 - Breaking down F-ups and why notes are important

Brought to you by my glaring shortcomings and Wellstar... again

What we’re breaking down: Preston’s massive mistake

What you’ll learn: The importance of reading notes to a financial statement

Why it matters: A lot of good and terrible information is hiding in the notes

Read time: 4 minutes (I made that up, haven’t even started writing)

First, a little announcement!

Since you are an amazing human who subscribes to this periodical, I am giving you exclusive, extended access to my upcoming:

Healthcare Breakdown - The Finance Course!

This course will be on-demand, run about 87 minutes (that’s probably not true, but it doesn’t matter because it will be more entertaining than the series finale of Game of Thrones), come with some awesome templates and pro-formas, and give you everything you have come to expect here and more.

If you want to go a little deeper and practice the skills I layout here so they become your own, this is for you.

I am closing sign-ups on Tuesday, so get in while the gettin’s good. This launch will be the lowest cost and consist of the crew nearest and dearest to my heart.

Thank you for your continued support!

Now let’s have some fun at my expense!

Let’s just lay it all out there.

I made a mistake.

In my last breakdown we looked at Wellstar’s balance sheet and did a bunch of mind-numbing calculations to see how awesome Wellstar is.

A couple of those calculations revolved around cash. One such calculation was Days Cash On Hand (DCOH).

As a refresher, this number tells you how long a company can keep running if all its revenue stopped immediately. It’s a measure of liquidity or immediately available cash. Like being able to loan a stack to your friend who needs to buy a new pair of limited Air Jordan’s in 15 minutes.

Soooooo, as you recall, Wellstar’s balance sheet looks like this:

And you know, because you diligently read everything I write, that everything below current assets, are considered long-term assets. Long-term meaning it takes longer than 1 year to turn those assets into cash.

Usually.

Lookie here, below current assets:

That stuff.

See, you have things like Property and Equipment. Your friend can’t buy sneakers with a C-Arm. That takes longer to turn into cash.

It also, theoretically, includes long-term investments. Those be here:

You may also see long-term investments simply labeled “investments” or “noncurrent investments” or whatever jargon the company dreamt up that decade. I would normally expect to see investments listed as such.

So, at face value for the days cash on hand calculation, Wellstar has $54M in cash and $4.3B in operating expenses before depreciation (from the income statement). Meaning it has a ridiculous 4 days of cash on hand.

Red flag. No way.

“Not a thing,” you (I) should have said. Instead, I went about my merry way and was just like, that’s weird, must be a timing thing. You’ll remember the Balance Sheet is a snapshot, a moment in time.

Here’s the most important thing to remember: If it looks off, something is wrong.

Your spider sense should be tingling. Either some malarkey is afoot or you have made a blunder.

Malarkey aside for Wellstar, in this case I made a blunder. All be it driven by some BS.

See what I did there? Balance Sheet… BS? Get it?

Anyways, no hospital is going to have 4 days of cash on hand unless that hospital is closing in 3.

Here is where the money is hiding, I mean mentioned:

Boom! In the notes!

I will paraphrase.

Wellstar uses cash, assets limited as to use, and some other stuff as primary liquidity because it can all be turned into cash within 1 year.

On top of that, it only keeps 2-10 days of immediate liquidity on hand. Remember, that’s the money piled on a mattress out back. That’s where the 4 days came from. At least I am not totally insane.

Why the frick don’t they put it under current assets though??

So glad you asked. If there is no intention to turn the assets into cash within 1 year, they leave current asset land to the land of long-term assets.

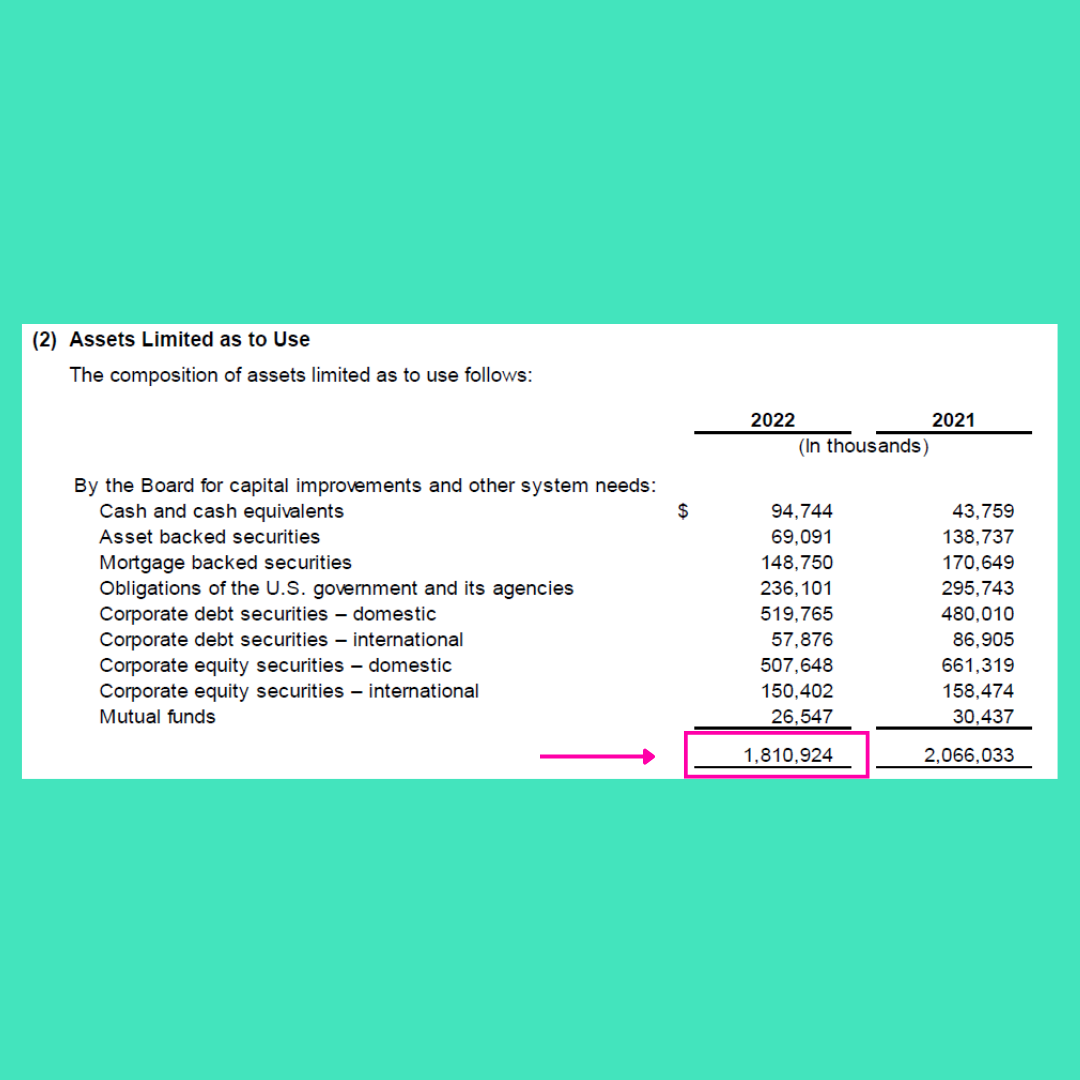

Now that we know what should be considered cash in terms of available liquidity, we need to find out how much. With a little CTRL+F for “Assets limited as to Use,” we find this:

Pro tip: use their words for searches. They are repeated in the notes.

These are the unrestricted, but board designated funds that are viewed as liquid and included as cash since they can be sold immediately and used for anything the board deems necessary.

$1.8B ready, willing, and able.

With this new information, we can see what the real deal DCOH is:

160 days.

Still not wonderful by Moody’s standards, but better than friggin’ 4!

Sweet sauce! I hope everyone enjoyed reading about my little whoopsie.

Learn from my mistakes:

1/ Always look at the notes.

2/ If something looks off, it probably is.