The Healthcare Breakdown No. 033 - Breaking down why it’s not all rainbows, unicorns, and endless cash flow for rural hospitals

Brought to you by Pandas

What we’re breaking down: The duality of our healthcare system

Why it matters: It doesn’t, just wanted to say duality. For realsies though, our healthcare system is based on income, that’s not good. For anyone.

Read time: As long as it takes to remember the name of that 1993 movie with Jack Black and Seth Green about roller blading (6 minutes for real though)

I know that I go on and on about health systems. They make all this money, their cash flow is bananas, they pay admin way too much or have too much admin, they invest all this money in hedge funds, yada yada yada…

But there is another side to this story. Because, while the country has over 6,000 hospitals, many of those hospitals serve rural communities. And what’s more, many of those hospitals serve low-income communities.

So, while it’s easy to talk the smack about UPMC, Kaiser, Ascension, Providence, Wellstar, Froedtert, Hasenpfeffer Incorporated, we can’t really talk about the likes of Atlanta Medical Center, Hancock Memorial Hospital, Florala Memorial Hospital, or Edward McCready Memorial Hospital in the same breath.

There are some predominant reasons why this is the case. One of which is the most salient.

Money.

And not just how much money the hospital has. That is a direct link to the patient population is serves.

Therein lies the rub.

The wealthy hospitals, serve the wealthier populations. They have the most power. They are the biggest.

Anyways, let’s look at the first order of business when it comes to supposing why a hospital is closing.

“Payor” mix.

The quotes are because so-called payors don’t pay for anything. They deny things. They take our money and tell us if they will use some of it to give to doctors on our behalf. Weird right?

Anyways, the mix shows us right away where the money is coming from into the hospital. And if you didn’t know, there is a pecking order in terms of the amount of these payments.

Here’s the breakdown:

Medicare: You can’t negotiate with Medicare. That’s right. Medicare pays what it pays and you can’t say mum about it. Lots of hospitals lose money on Medicare. Whether or not you should have a better cost structure is a topic for another day (the answer is yes). The fact remains that most hospitals lose some money on Medicare reimbursement.

Medicaid: These good old boys, really stick it to you. I don’t care how good at cost controls you are, it’s hard to make money on Medicaid when running a hospital. Partially because of the patient population, which, if we invested in properly outside of the traditional healthcare system wouldn’t have the same problems, but I digress. They don’t pay enough.

Commercial: Ahhhhhhh, relief. Commercial insurance contracts are going to pay like 300% or more than the Medicare rates. That’s right, health systems negotiate rates to wipe out the losses from Medicare and Medicaid and then some.

Pecking order achieved.

Here is an great example of how this plays out:

Vail health system is a small health system in what would otherwise be considered a rural area. Although you and I know that Barnes, Barron, Brighton, Braydon, and Bennet have been skiing the area in their grandfathers’ cabins since they were yay high.

In other words, Vail has a lot of rich people.

Check out its mix:

Let’s look at, in dollars, how insignificant the worst claims processor is:

$7.7M in Medicaid net patient revenue.

Or for those keeping track, 1.88% of total net patient service revenue.

Oh, also if you are keeping track and are thinking that 1.88% is higher than 1%, you’re right. The main difference, since you didn’t ask, is that net patient revenue sources (the dollar amounts) include what the patient owes but attributes it to a certain processor. The percentage mix is a receivable breakdown and breaks out what a patient owes as a receivable. That drives the primary difference between the amount and the percentages.

So, they’re still pretty close from a mix perspective.

Now, let’s compare that to a hospital that doesn’t serve such a yacht-owning population.

Hazel Hawkins Hospital is an San Benito County California. It declared bankruptcy at the beginning of the year.

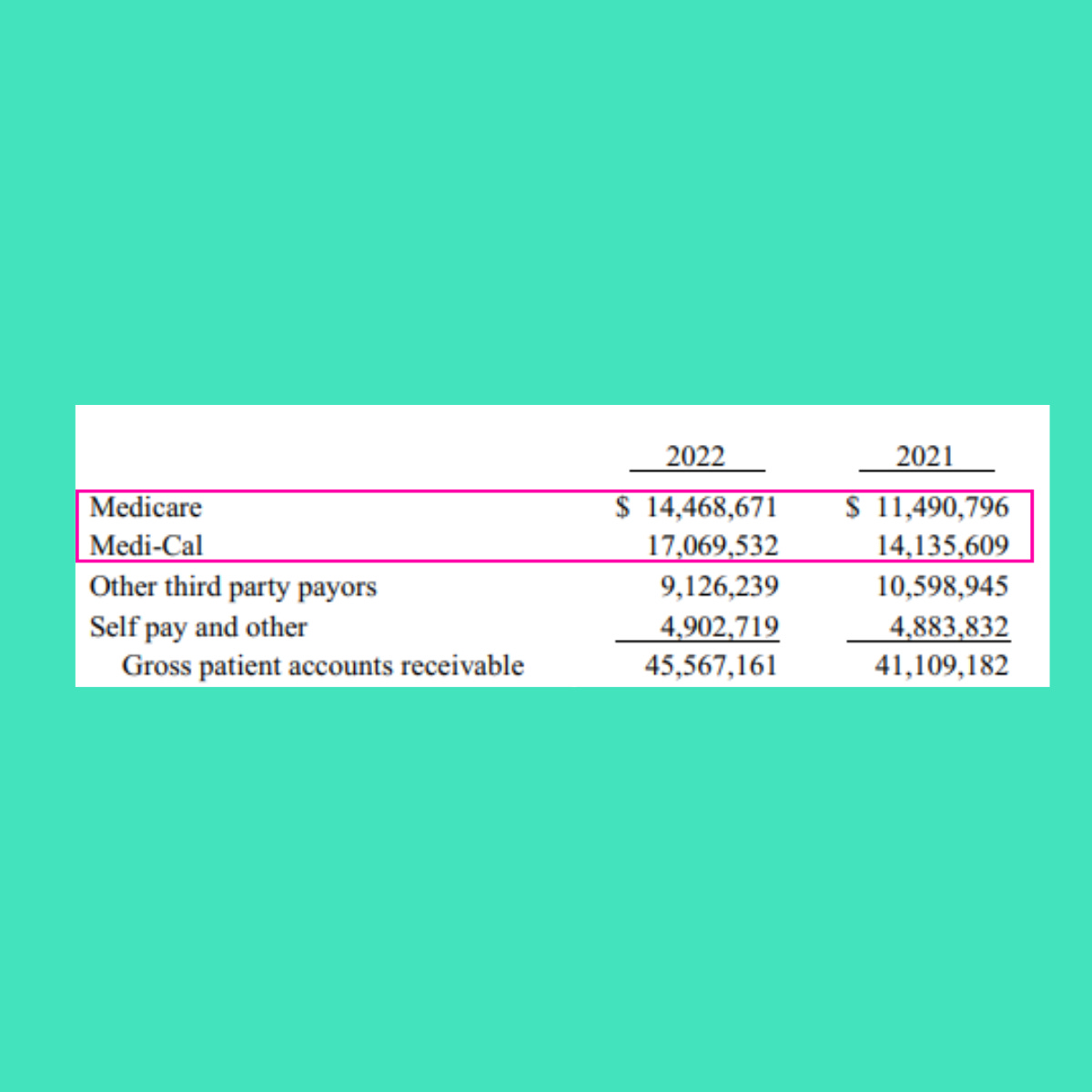

Here’s its mix:

To spare you getting your TI-89 out, that’s 69% of payments coming from Medicare and Medicaid.

37%, just from Medicaid. They call Medicaid Medi-Cal in California, cuz you know, creatives and stuff.

Let’s talk for a second about the vicious cycle of all this.

Medicaid pays the worst reimbursement rates. It also is the only insurance that lower income earning individuals can get. When your income is lower that usually means you also don’t have as much access to healthy food, may have housing issues, and other things to contend with that all negatively impact health.

What that translates to is a person who needs more care. Not less. That is then going to put a disproportionate burden on hospitals that serve primarily low income communities. The hospital takes care of these patients with more health problems more often, and gets paid the least for it.

Now, there’s another rub here. While smaller and rural hospitals serve lower income populations, the hospitals themselves are not behemoth 11 hospital systems covering multiple states.

In the world of business and negotiation, we would call that a lack of leverage.

If Hazel Hawkins enters into contract negotiations with Cigna, Aetna, United, Humana, or BCBS, and starts demanding rates 300% over Medicare, the big suits are going to very kindly hand them an Evian as they escort them to the door. Laughing all the way. And not the yule-tide season, good kind.

What does United care if some critical access or rural hospital drops its contract? That’s right, they don’t.

Now we have created this whirlpool that drains money.

People can’t pay or have insurance that underpays. Commercial processors don’t care so they also underpay. Then the hospital closes. And no one really wins.

Here’s one last graphic to drive the point home:

Hospitals at risk of closing get the shaft from everyone, except Medicare interestingly enough. That’s because Medicare will pay additional subsidies for hospitals taking on a disproportionate share of low income patients or those with certain designation like a critical access hospital.

The cycle extends beyond the hospital walls and ripples through communities as well. Not only will communities lose access to healthcare, but when a hospital closes, a major employer in the area closes.

That means job loss. That means lower income. And we now know how that translates into worse health and hospital closures.

And that’s all I have to say about that.

The healthcare spiral is well afoot. The gap will keep widening based on peoples’ income levels. The income a person earns is directly tied to the type of insurance they have. And the type of insurance has everything to do with how much money the hospital will get paid.

Huh, guess I has a tiny bit more to say…

Now go top off that mimosa and put on Looney Toons. It’s the perfect Sunday.

Love you.

This is an interesting take on the healthcare spiral, as you put it. However, I think there should be a little more context given, especially as it relates to for profit vs non-profit health systems and the requirements for caring for ALL patients. There's also a lot of context needed for critical access hospitals and their different operating and reimbursement models. Good high-level perspective but needs added context.