The Healthcare Breakdown No. 035 - Breaking down Cigna’s $11.3B stock buyback… and what Warren gets wrong about it

Brought to you by powder blue tuxedos

What we’re breaking down: Cigna’s $11.3B stock buyback… didn’t I say that already…. sorry

Why it matters: That’s $11.3B in care and premium reductions you aren’t getting

Read time: How long it will take you to find the people who came for me on my last LinkedIn post and figure out who hurt them (7 minutes for real though)

All right, let’s just get it all on the table. Happy New Years. I love you and hope that all your dreams come true in 2024.

Also, I got some interesting heat on LinkedIn after my post that mentioned Medical Loss Ratios. The contention seems to be… “well, then, what’s the right MLR?”

I don’t think that’s the right question and not much of a cogent argument or rebuttal.

The MLR is the cornerstone of an insurance carrier’s profitability. It’s basically its gross margin. Gross margin is the grandpappy of profit, the starting point. And yes, the ACA mandated minimum MLRs, which led to a whole host of unintended, though what should have been obvious consequences. Namely, when you lock-in a max profit percentage, the only way to increase the gross amount of those profit dollars is to raise the top line. That means higher premiums and more expensive healthcare.

Anyways, this issue is not about MLRs, but since they garnered so much attention, I figured I would start here. The BUCAHs do their level best to come in right at the wire of the minimum MLR they are required by law and spend as little on claims as possible. Why else would they report on it as a key metric?

See, it’s on a slide.

It’s also the place to start when talking about buybacks. Cigna, as we are discussing today, is buying back $11.3B worth of its own stock. How is that possible?

Well by earning premium dollars and paying only the what they are legally obligated to pay. And what we will find out in a few issues, a number that is largely made up and completely inflated.

Ok, now on to the buyback!

Cigna was recently all hubbub in the news because it was going to merge with Humana. Or buy it. Or some such nonsense.

The news swirled like the center lever of a soft serve machine for about 2 weeks.

Here’s how it all went down from a share price perspective:

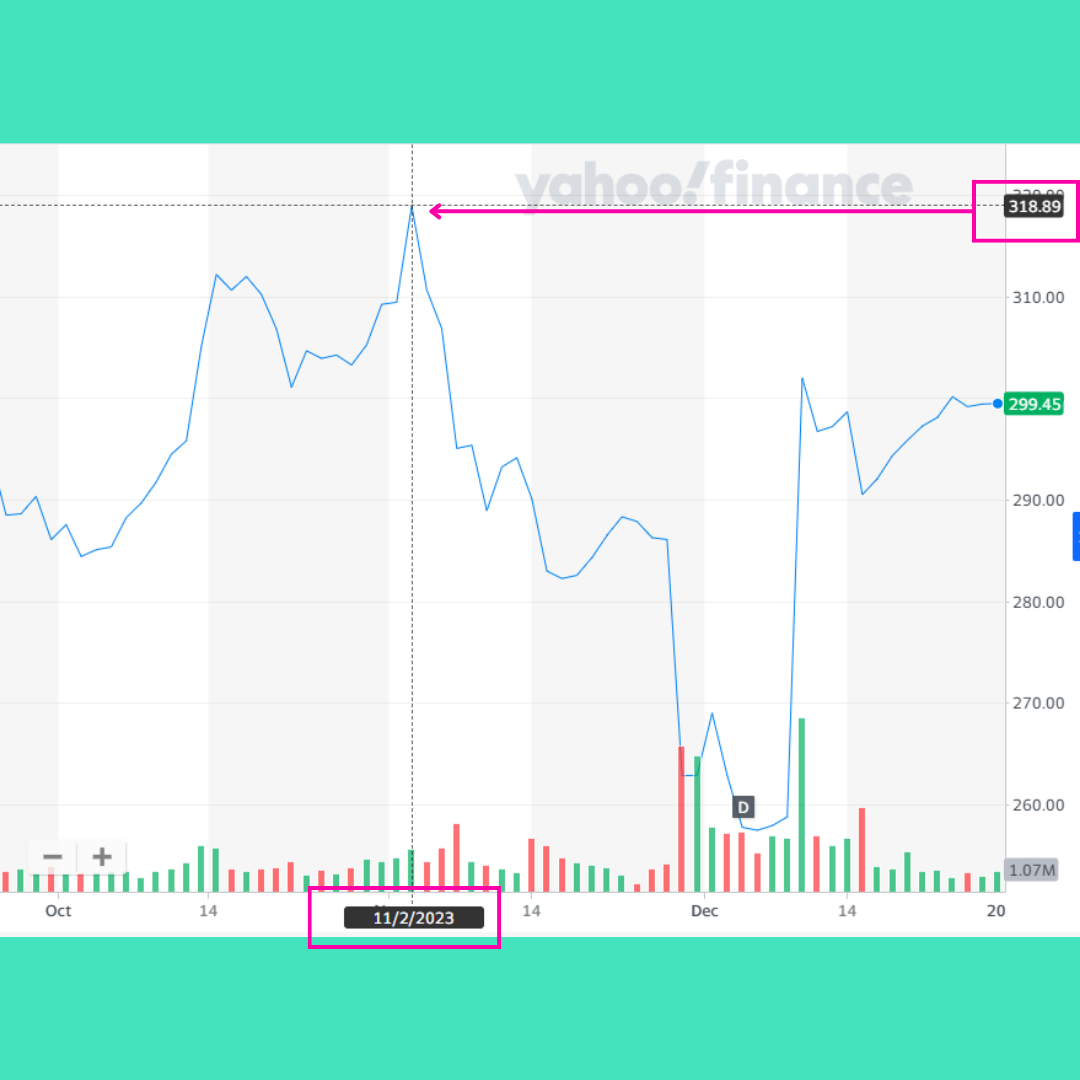

Before the Humana potential deal was announced…

Riding high on strong Q3 earnings report! Weee!

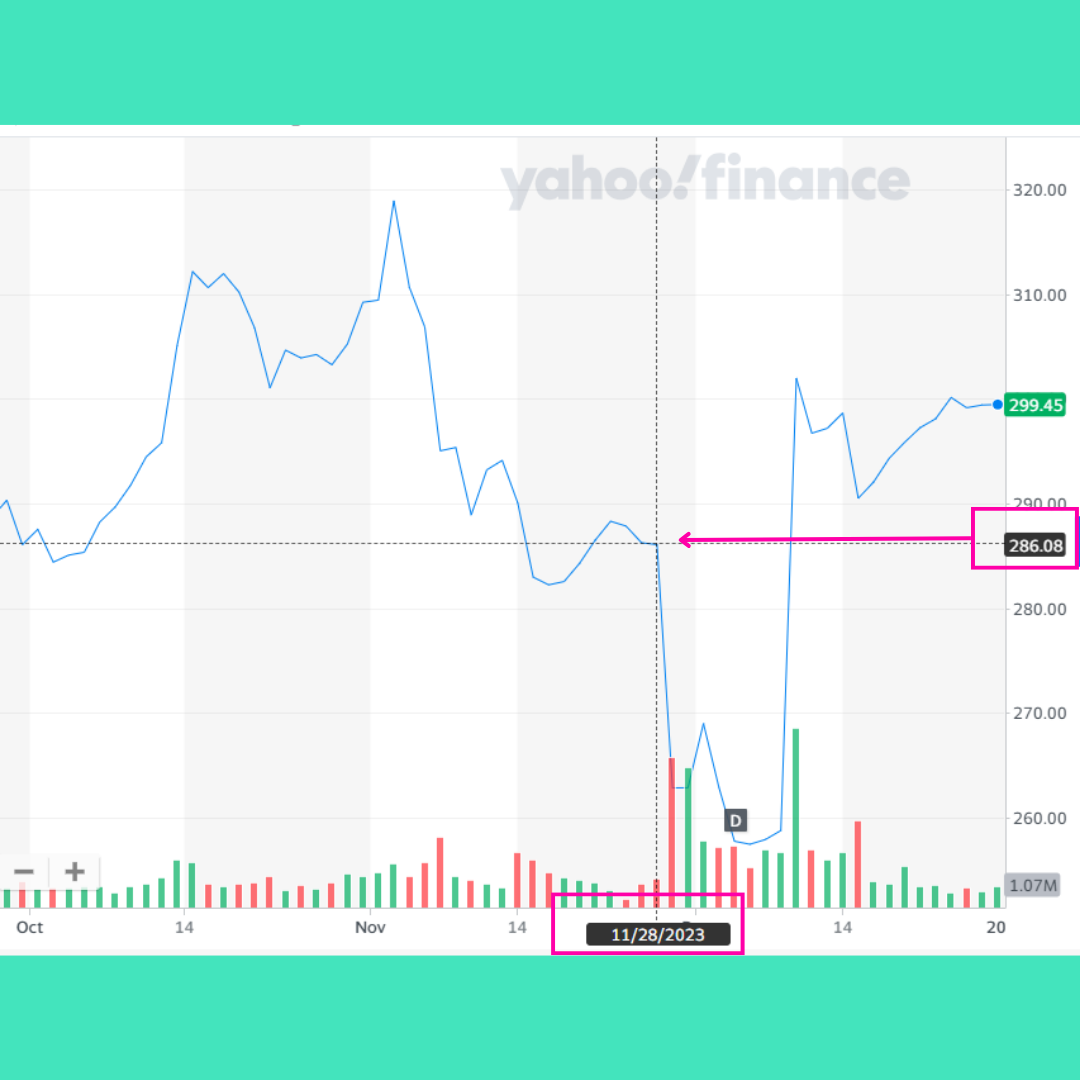

When the Humana deal was announced…

Uhhh, wait. Things seem to be going the wrong way, but announcing a mega merger will totally help!

After the deal announcement…

What the what? That did not work.

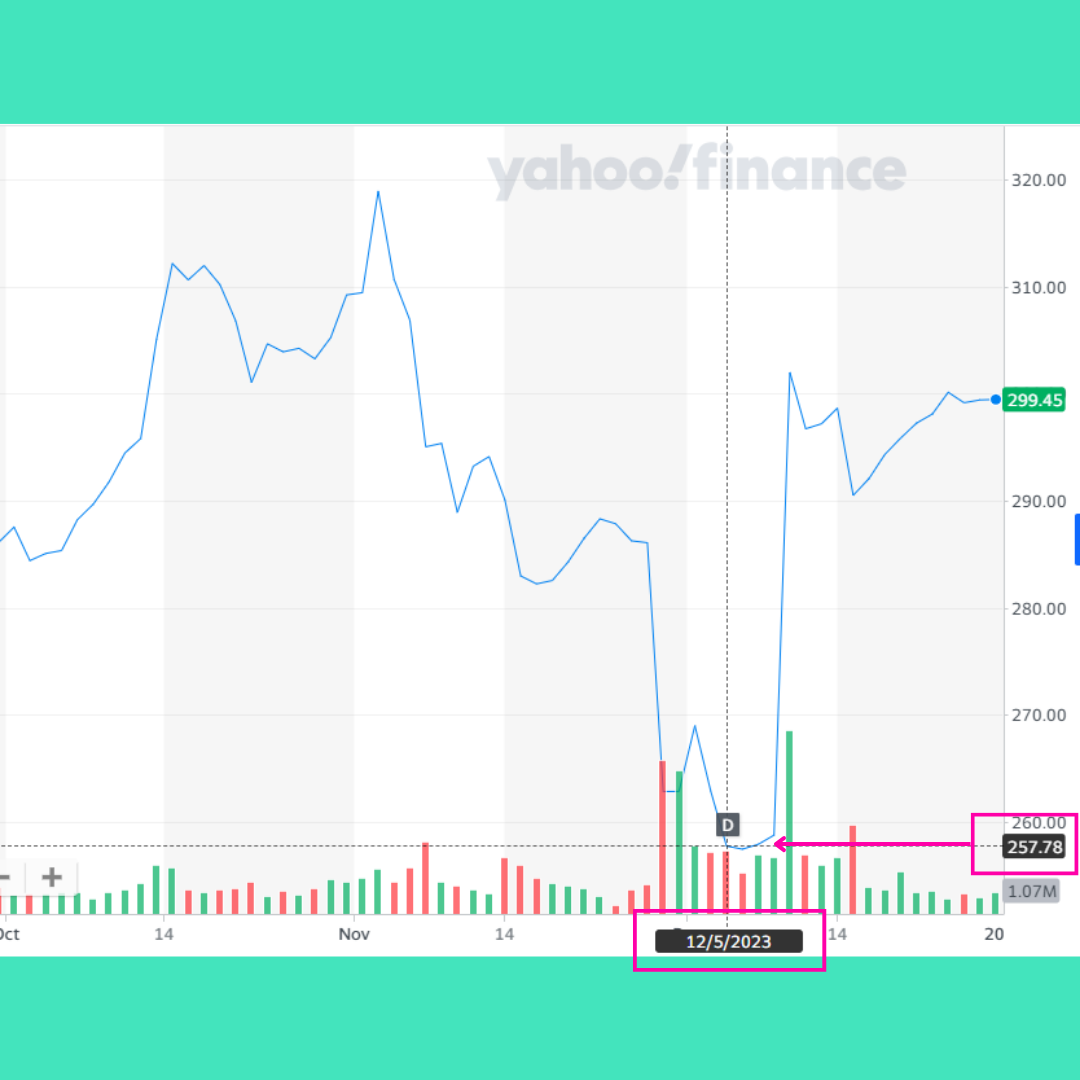

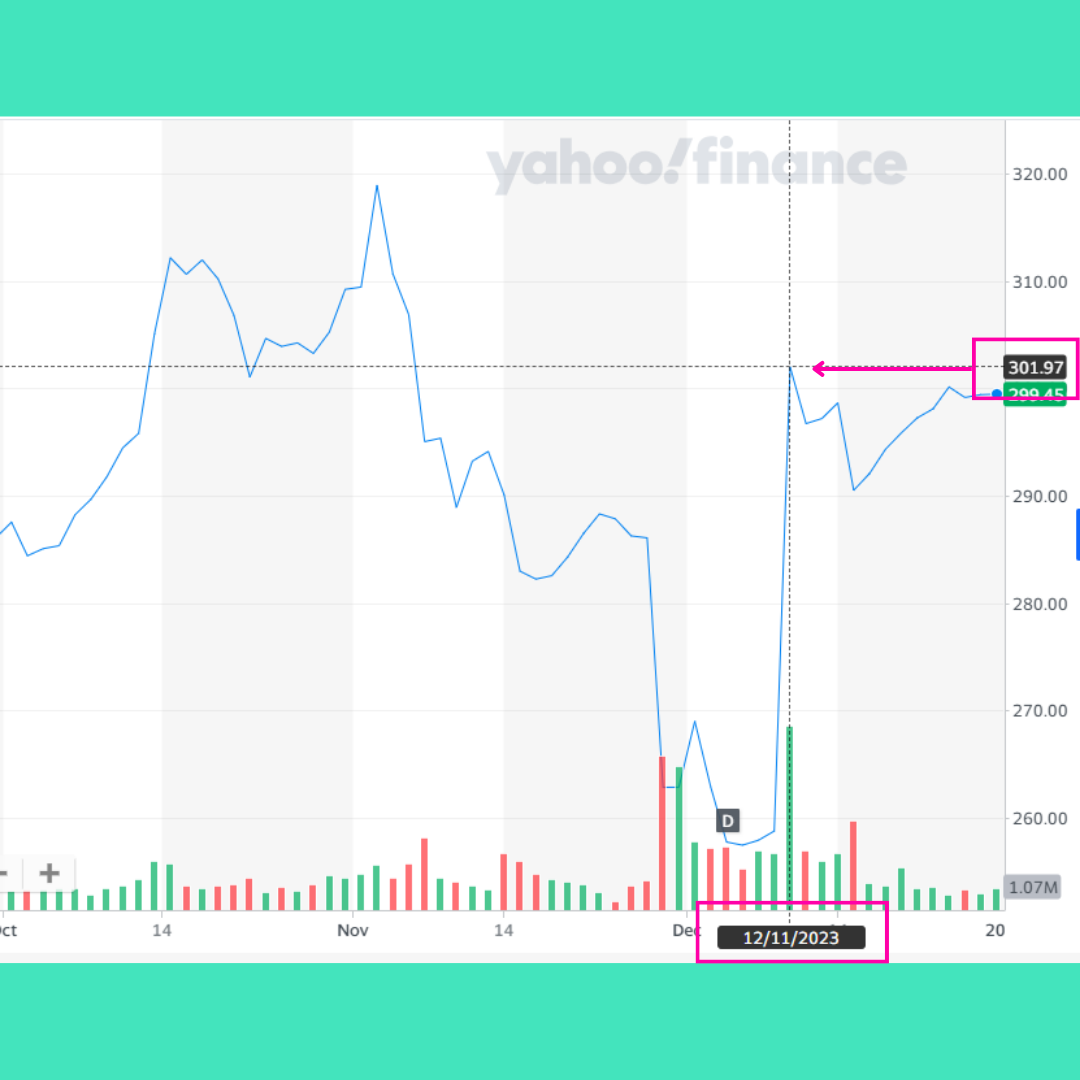

After the deal was unannounced and the buyback was announced…

There it is. Woohoo! We’re back baby!

Let’s dive in, first to the numbers and then to the implications.

So, after Q3 earnings, which were “decent,” Cigna’s share prices began to drop. I put “decent” in quotes, because beating expectations doesn’t mean you’re doing well in the eyes of the market. Profits were down, so share prices dropped.

Or people saw a ceiling and decided to sell. Or people decided to buy GameStop. Or some hedge fund managers needed a bigger Christmas Yacht. There are a million reasons for share prices to decline.

But, when you’re a shareholder, specifically one with a lot of interest in the company to do well, you want that share price to go up. Obvs.

Someone like the CEO David Cordani perhaps, who owns about 590,000 shares. Which at some point at or near the time of this writing, post share price rebound, were valued at about $173M.

Not a bad slice of cheese. Seth.

But as you saw, prior to the buyback announcement, share price was going down and bottomed out at $257.78 per share, bringing poor Dave’s net worth to a paltry $152M.

A $21M difference.

And this was after the Humana deal announcement.

It seems that the market did not care for Cigna buying Humana. And since publicly traded companies exist to deliver shareholder value, Cigna made a move.

It abandoned the acquisition and announced a massive stock buyback instead.

$11.3B massive.

Guess what? The market loved it.

Uncle Dave’s net worth went up $21M in a day.

How does this happen?

It’s simple mechanics although it might seem counterintuitive. When a company buys back it’s own stock it is taking shares out of the pool of outstanding stock.

When that happens shares immediately become more valuable.

Three big reasons:

Earnings per share goes up. There are less shares, so more earnings are allocated per share. Nothing changed, but it feels nice. Technically, that’s a more valuable share.

More liquidity. As a shareholder you know there is a deep pocketed buyer out there. There’s value in liquidity.

Supply and demand. When there’s less, things become intrinsically more valuable. Saw that on a bumper sticker once.

Interestingly, it also decreases shareholder equity.

Looky here…

The brackets, they’re negative doohickies.

It’s negative because the company has spent its cash (an asset) to buy something. Its own stock in this case. Therefore the company has reduced its Assets. Since balance sheets must balance, shareholder equity is also reduced.

It also makes sense because shareholders no longer own that cash, so equity is reduced.

Good old balance sheets.

Well, great. Who cares?

Cigna wants to buy back it’s own stock. David what’s his name is richer. Yada, yada, yada. Yachts and things.

Let’s turn to the Oracle of Omaha for some additional words of wisdom on the topic…

“The math isn’t complicated: When the share count goes down, your interest in [the] business goes up. Every small bit helps if repurchases are made at value accretive prices. Just as surely, when a company overpays for repurchases, the continuing shareholders lose. At such times, gains flow only to the selling shareholders and to the friendly, but expensive, investment banker who recommended the foolish purchases.

Gains from value-accretive repurchases, it should be emphasized, benefit all owners – in every respect. Imagine, if you will, three fully-informed shareholders of a local auto dealership, one of whom manages the business. Imagine, further, that one of the passive owners wishes to sell his interest back to the company at a price attractive to the two continuing shareholders. When completed, has this transaction harmed anyone? Is the manager somehow favored over the continuing passive owners? Has the public been hurt?

When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive).”

Not one to disagree with the guy who will hand you a sieve on a baking tray when you need something to hold liquid, I, well, disagree.

In part.

I don’t disagree that buying back stock is bad. Or that even a health insurer that is a publicly traded company buying back its own stock is bad.

That’s why it exists after all. Its job is to allocate resources effectively in order to produce the best returns for shareholders.

The issue is in the fundamentals. In the system. In the people who are, indeed, hurt by this.

While states don’t spend this much on Medicaid, a single company, whose other purpose is to ensure and enable the health of the people it serves, can spend billions on buying back its own stock in order to make itself and other people wealthier.

That’s $11.3B that could be making a dent in the $100B in medical debt owed in this country.

$11.3B can cover annual premiums for 515,000 families.

Or lower premiums for current covered individuals. Or lower operating costs for businesses that are struggling to reinvest because of runaway healthcare costs.

Heck, it could even pay for 3.8M peoples’ $3,000 deductibles.

Or, you know, increase shareholder value. That’s cool too.

Man, I don’t think I’m going to get invited to the New Year’s yacht party this year.

Anyways. I love you. I appreciate you being here. Thank you for an incredible year.

Can’t wait to keep smack talking in 2024.

See you out there!

It IS a nice slice of cheese. Great issue @preston!