The Healthcare Breakdown No. 052 - Breaking down how to make more while doing less in your clinical practice (no, this isn't click bait)

Brought to you by Centivo

What we’re breaking down: Costs and contribution margins in clinical practice

Why it matters: Applied correctly, these fundamentals can lead to better care and higher profits

Read time: Depends how many times you doze off while reading this (8 minutes for real though)

This episode is brought to you by:

Hungry for a change?

Join our Virtual Lunch & Learn!

We'll dig into how we're saving employers an average of 21-33% on total cost of care. And send you a free lunch!

With Fall around the corner there are two things on everyone’s mind. Flu shots and pumpkin spice lattes.

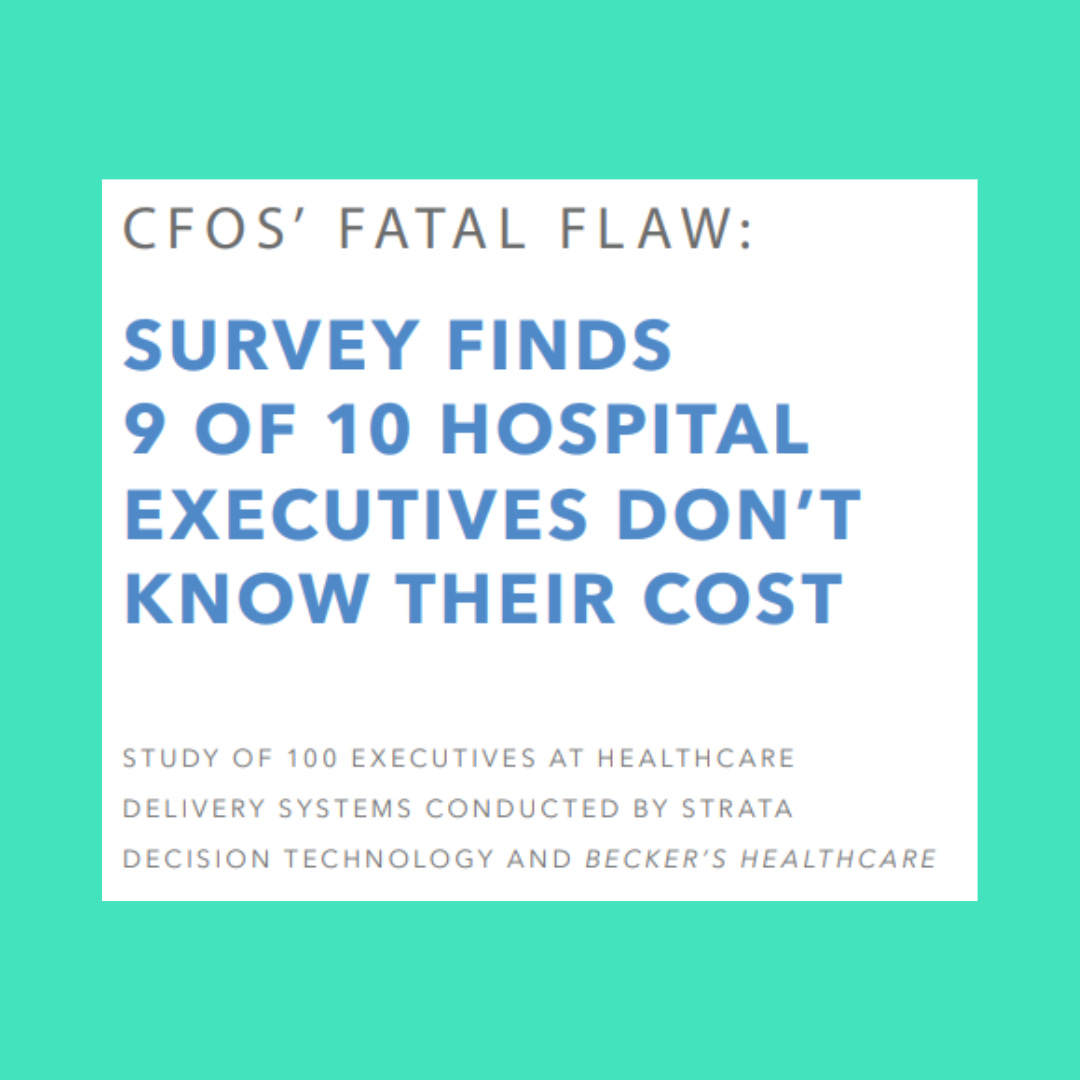

Naturally there is another topic on everyone’s mind. A perennial favorite, the wild costs of healthcare. Funnily enough, despite costs being out of control and everyone constantly talking about costs, you may be surprised to learn that most healthcare leaders don’t know their own costs.

And as you will see, not knowing your costs leads to all sorts of issues. So today we’re talking about contribution margin and activity-based cost accounting.

First, let’s talk about why this is important in business in general and then why it matters in healthcare. If you don’t fall asleep or pull your eyelashes out first, you can stick around for the “how to do it” part.

Minor disclaimer: If you are reading this, you probably know where I stand on the issue, but for now, we’re going to table that and get real businessy.

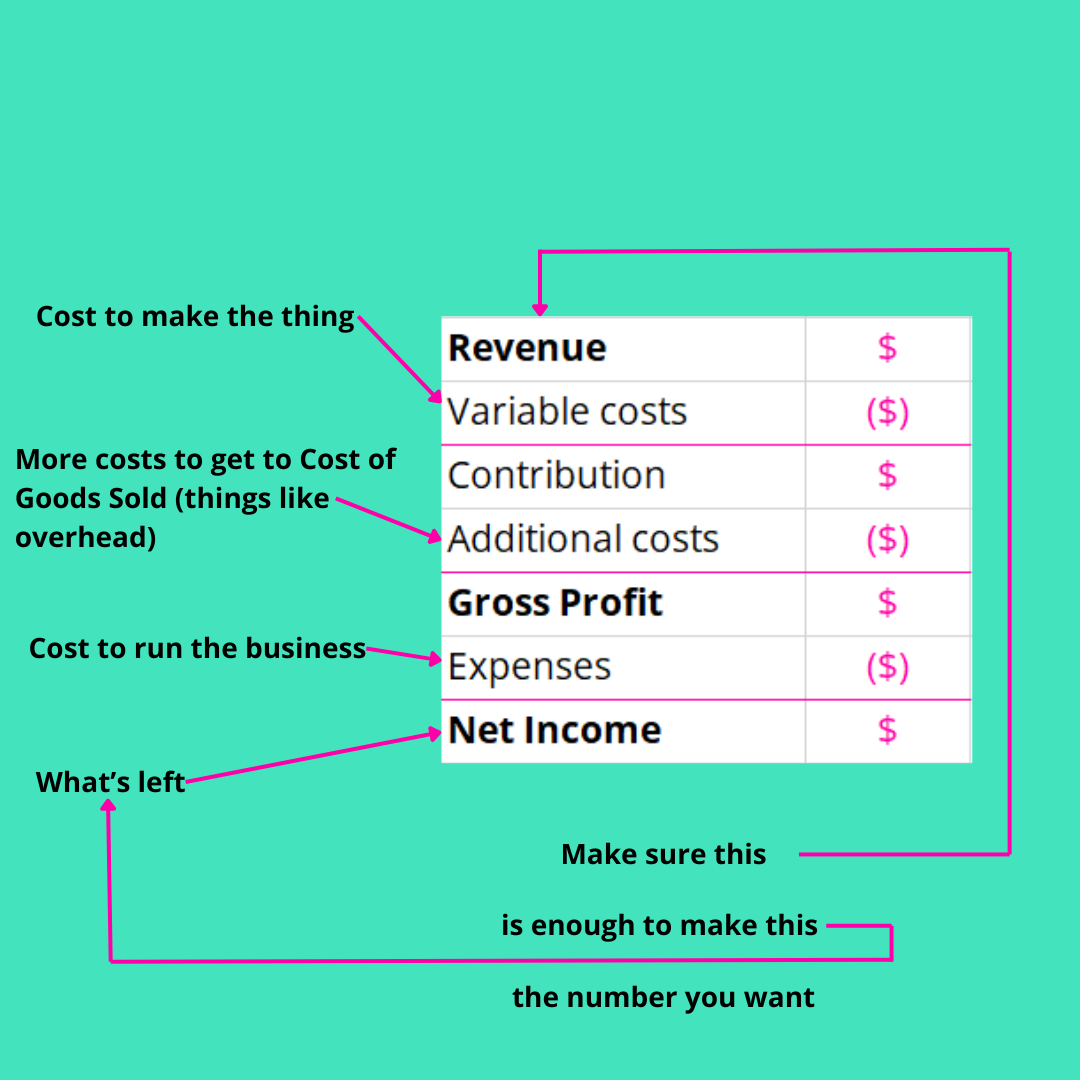

Let’s start from the very beginning. Contribution margin is revenue from one thing minus the direct variable cost to make the thing or provide the service. It’s essentially the very first step of profitability, before you add in things like overhead.

It basically goes like this:

Why am I bothering telling you so?

The delta between price and cost is how you make money and grow a business. With no delta, or very little, you are stuck.

You can’t invest in more people. You can’t invest in new tech. You can’t open a second location.

And the issue that most people face is they don’t know their costs at all. Well, they kinda do, but only at the end of the day.

Check out the madness:

Here’s a link if you’re into that sort of thing.

Now, it’s not like these titans of Excel don’t know how much the whole kit and caboodle costs to run at the end of the day. But they have no idea how much it costs to take someone’s old decrepit knee cap out and slide a new one in.

They definitely don’t know what it really really costs to take out your gallbladder.

Any why don’t they? Well because it’s hard AF.

Just think about all the complexity going down in an OR. You have team members all with different salaries. One case is done in 37 minutes and another takes 2 hours. One uses 7 liters of irrigation fluid and another uses 1. One has complications and requires assistance from another surgeon and the other doesn’t.

It’s bananas out there.

Then, you have this overhead nonsense. It costs money to keep the lights on, run the A/C, play the AC/DC, and keep those glazed carrots in the surgeons cafeteria warm. Who pays for all that jazz?

I know what you’re thinking at this point, “I don’t want a valuable lesson, I just want ice cream.” But stay with me.

When you have multiple service lines and multiple types of visits or procedures within that service line, if you don’t know the costs associated with each one, you can’t make well informed financial decisions.

So say you are an awesome-sauce independent practice and have defined 3 service lines. Within those service lines you bill for roughly 5 procedure/visit types each. Your P&L looks pretty good at the end of the day, but can never seem to grow past a certain point.

Well, if you looked at every service line individually, you might find that one of them is 15% less profitable than the rest. A further drill down reveals that 2 of the procedures are losing you money.

Bingo. Stop offering those procedures and profitability will magically improve.

We often think that less revenue is bad. That’s not true. Less of the wrong revenue is good. You can only find the wrong revenue if you know your costs based on the specific service.

Ok Sam I Am, now that we know why we should do this, how do we do this?

While it will be different for different care settings, the principles are the same. And if you’re interested you should check out the work that Dr. Vivian Lee did at the University of Utah. And after you are impressed by that, you should check out her book.

Let’s imagine you are in private practice and ready to take things to the next level. The example above gives you a little perspective into how this helps, but where do you start?

Well, dust off your algebra books cause you may recognize this little ditty:

y=mx+b

Yup, that would be the old linear equation. And there you were in 6th grade thinking to yourself, why the heck fire do I need to learn this junk? You’re welcome Mrs. Sniderman.

Here’s how you use it. With pictures, naturally.

Step 1: Get all your cost data in one place. You need to collect a few months of it.

Ok no picture here.

Step 2: Get all your productivity data in one place. So all the appointments. That patient volume.

Or here… The pictures are coming though, promise.

Step 3: Fire up Excel. Put each data type in a column. By week if you like. Doesn’t matter too much, but you want enough data over time. Don’t worry about dates. We are just looking at the relationship.

Step 4: Scatter plot that sucker.

Step 5: Insert a trendline

Step 6: Get the equation

Now, drumroll, you have an estimation of your variable costs and your fixed costs. That’s the magic sauce in contribution margin.

In this totally made up example you have an average variable cost per patient of $111.35.

You have fixed costs of $2,544.60.

If I know how much I average in revenue per patient, I can quickly see how many patients I need to see on a weekly basis to breakeven.

In this rough example, if my average revenue per patient is say, $150, then my contribution margin is $150 - $111.35 or $38.65.

To cover my fixed costs I need to see 66 patients a week.

When you have your fixed costs (those are the costs that don’t change no matter how many patients you see) and you know your variable costs (the costs that change depending on volume) you can determine:

How many patients you need to see to breakeven.

The price that things need to be (which impacts number 1).

If something has the chance to be profitable or if you should move on.

That’s the quick and dirty. That’s how you can probably approach this if you are running your own practice or in a mid-sized group or smaller.

Looking to grow your practice, but not sure where to start? Setup a consult with Forward Slash / Health. They even offer a complimentary financial analysis of your practice.

In a hospital or large multi-specialty you may want to approach things from a bottom-up activity basis. That’s what Dr. Lee did so well.

The basics is you have to track everything over time. For everything. How many lap sponges. How long the scrub tech was in the procedure. How long the procedures took. Ev. Er. Ry. Thing.

Ya, cumbersome.

But the results speak volumes. The University of Utah was able to save millions, become more efficient (more revenue), and improve outcomes.

Because what happens when you have an unnecessarily long length of stay, generally? Ya. Worse outcomes, less money, and a lot of grumpy people.

It may seem boring and like doing this type of exercise would make you a fusspot. But sometimes boring things can be fun. Chili knows.

Here are the fun parts:

1/ when you know your costs, you can control them much more effectively. That increases profit. That means as a practice owner you make more money without doing more. Yay.

Now don’t go all Ralph de la Torre and cut costs that are necessary. That’s a fast track to yachts, I mean jail. Well, maybe not fast, but eventually. Maybe.

2/ You can make better financial and strategic decisions. Wanna grow? How much is it going to cost to start the new clinic? How many patients do you need to bring in to make it profitable? How profitable can you be in the first year?

Exactly, get them costs and contribution margin. Then those questions aren’t scary. Still annoying. Not scary though.

3/ You have leverage when asking for investment from leadership.

Ohhhhhh buddy. The hidden gem. I just have to expand on this a little with a creative application.

Let’s say you are running a department and want some raises for your people, but the administration whines and says there is no money because costs are too high. Remind them, semi-politely, of your contribution margin. And further more, you don’t agree with the overhead and administrative cost allocation to your department. In fact, you can politely this time, ask for the breakdown of those cost allocations so you can see exactly why they can’t afford any raises at this time. You can also suggest that if they had a better handle on costs they could lower them and then afford to pay the people who actually drive revenue more.

That’ll be a fun convo. When management doesn’t have a good handle on costs they can’t manage anything.

All right, this is getting too long. If I had more time, I would have made it shorter.

You stay classy, planet earth.

Fantastic- and this time I understood all of it!

Fantastic analyses & examples, thank you for the brilliant insights!